From fake news to bots: impressions from this year’s Europcom

November 22, 2017

Evaluating the Communication of Cohesion Policy

December 7, 2017Many believe that the Cohesion policy could counterbalance the negative impact of the EU crises having diverging impact on different member states crises for the identification with the EU.

The case of Slovenia shows that its potential should not be overestimated as it also the crisis that is dictating perception of the Cohesion policy.

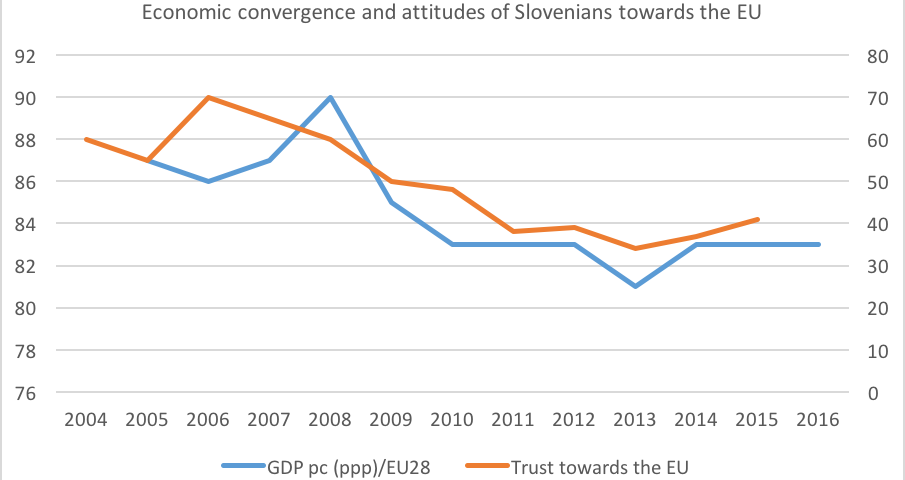

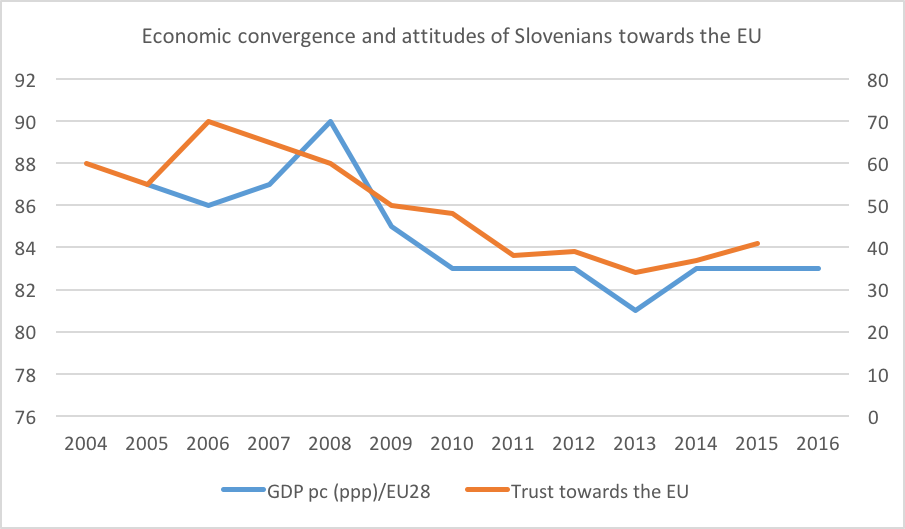

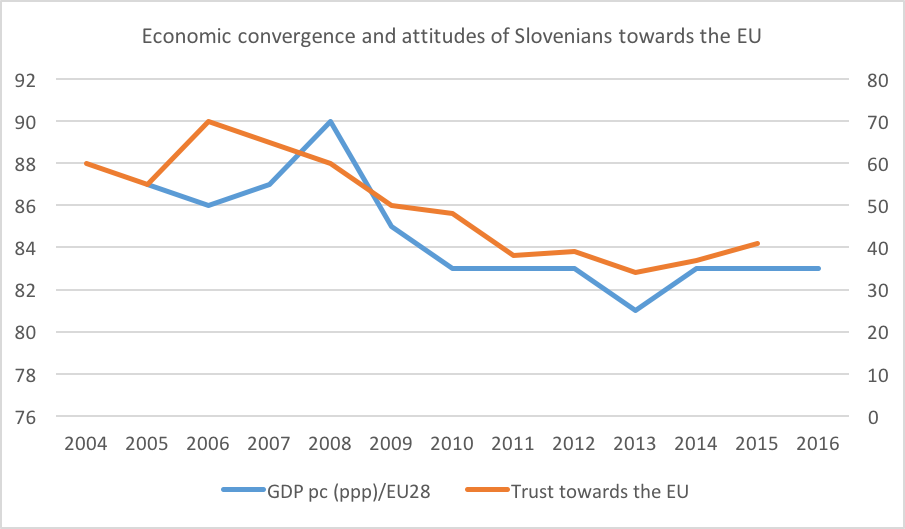

Being the most developed Central and East European country that entered the EU in 2004 and the first to enter the Eurozone (in 2007), Slovenia was quick to catch-up with the EU development level. By 2008, its per capita GDP was at 90% of the EU average. At the time, Slovenia was constantly amongst five member states with the most positive attitudes towards EU policies, including the Cohesion policy. Slovenia benefited from the EU’s (pre-accession) structural support programmes since the early 1990s. For the 2007-2013 programming period, Slovenia was granted €4.2 billion, which was well over 10% of its GDP. With most of the money earmarked for infrastructure and R&D, Cohesion policy was expected to give an additional boost to the country’s economic development.

In 2009, in the context of the global financial and economic crisis, Slovenia, being a relatively small and open economy, faced one of the strongest economic downturns in the EU with a GDP decline of 9%. The specific causes of the depth of the recession were bubbles in sectors such as real-estate, fuelled by under-priced loans by state-owned banks. After a brief recovery in 2010-2011, in the context of the Eurozone crisis, Slovenia faced a secondary recession. The attempt of the government to keep the economy running resulted in current account deficit reaching 15% of GDP in 2013. In 2015 public debt, which used to be one of the lowest in the Eurozone, was at 83%. The economic growth only returned in 2014. In terms of convergence, Slovenia was, however, back to where it was before its accession to the EU.

Being the most developed Central and East European country that entered the EU in 2004 and the first to enter the Eurozone (in 2007), Slovenia was quick to catch-up with the EU development level. By 2008, its per capita GDP was at 90% of the EU average. At the time, Slovenia was constantly amongst five member states with the most positive attitudes towards EU policies, including the Cohesion policy. Slovenia benefited from the EU’s (pre-accession) structural support programmes since the early 1990s. For the 2007-2013 programming period, Slovenia was granted €4.2 billion, which was well over 10% of its GDP. With most of the money earmarked for infrastructure and R&D, Cohesion policy was expected to give an additional boost to the country’s economic development.

In 2009, in the context of the global financial and economic crisis, Slovenia, being a relatively small and open economy, faced one of the strongest economic downturns in the EU with a GDP decline of 9%. The specific causes of the depth of the recession were bubbles in sectors such as real-estate, fuelled by under-priced loans by state-owned banks. After a brief recovery in 2010-2011, in the context of the Eurozone crisis, Slovenia faced a secondary recession. The attempt of the government to keep the economy running resulted in current account deficit reaching 15% of GDP in 2013. In 2015 public debt, which used to be one of the lowest in the Eurozone, was at 83%. The economic growth only returned in 2014. In terms of convergence, Slovenia was, however, back to where it was before its accession to the EU.

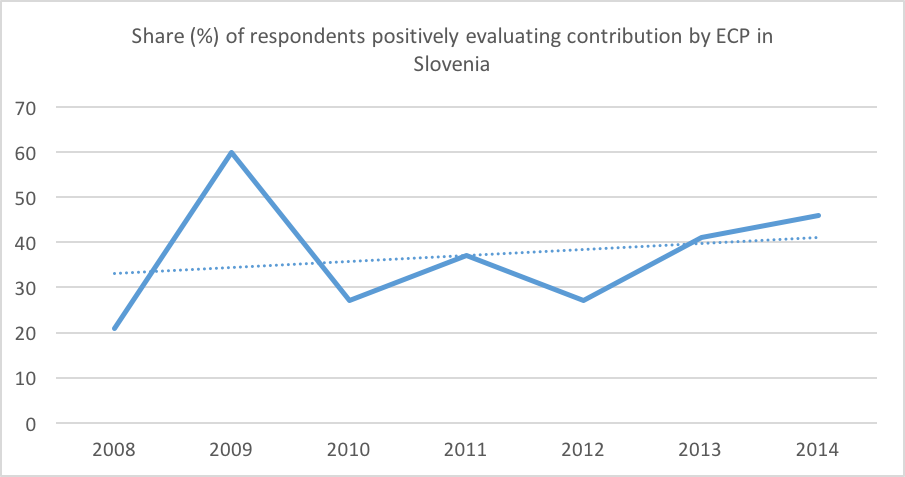

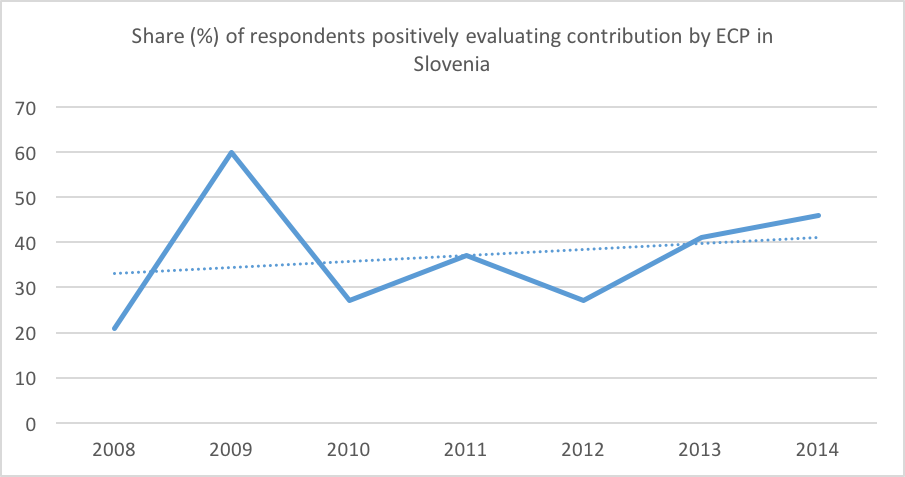

The Euroscepticism grew and the Cohesion policy was no exception (see the Graphs below). Investments into infrastructure that were part of the policy were linked with credit booms in construction. As many of the private enterprises that received EU supports were highly indebted or even went bankrupt, it was not easy to build a positive story around these either. Even when European funds were used to address unemployment, e.g. via subsidies for self-employment, labour unions voiced criticisms, arguing that this was a neoliberal approach towards employment policy, a part of the savings dictate from the Brussels, that was in fact dismantling the welfare state. Moreover, domestic political elites trying to avoid blame for painful measures did not hesitate to point fingers at the EU.

There were also more direct links between the crisis and the Cohesion policy, ranging from delays in implementation due to lack of finance to instability in the governance structures in the period 2011-2013 as a result of political turbulence. With the crisis, existing problems of the Cohesion policy in Slovenia, such as low project sustainability (i.e. dependence on the supports), came even more affront. Finally, the total contribution of the EU funds in the new programming period 2014-2020 was reduced by €1 billion. The strongest cut was made to the financing of the small regional bottom-up projects, which in past provided for recognisability and support for the Cohesion policy in local communities.

Nevertheless, some positive things did come out of the crisis. With no money to continue with the Cohesion policy advertising campaign that was for the first (and the last) time implemented in 2009, in 2010, a decision was made to engage with experience based promotion by holding events at the sites of the investments and inviting local people to take part, thus drawing attention of media. Communication focused on particular contributions and individual experiences helped in de-linking the policy from the macroeconomic trends and structural reforms where, ironically, Cohesion policy was increasingly filling the gap left by the other policies and was consequently also taking the blame of the various policy failures.

While the Cohesion policy has an important stake in keeping the EU together, as the Slovenian case shows, it cannot and should not be seen as a mechanism for fixing all of the problems related with the asymmetrical crises. Rather than that, to avoid the expectations-capability gap, it should be based on reasonable expectations concerning specific contributions with a potential of spin offs and inspiring broader change

There were also more direct links between the crisis and the Cohesion policy, ranging from delays in implementation due to lack of finance to instability in the governance structures in the period 2011-2013 as a result of political turbulence. With the crisis, existing problems of the Cohesion policy in Slovenia, such as low project sustainability (i.e. dependence on the supports), came even more affront. Finally, the total contribution of the EU funds in the new programming period 2014-2020 was reduced by €1 billion. The strongest cut was made to the financing of the small regional bottom-up projects, which in past provided for recognisability and support for the Cohesion policy in local communities.

Nevertheless, some positive things did come out of the crisis. With no money to continue with the Cohesion policy advertising campaign that was for the first (and the last) time implemented in 2009, in 2010, a decision was made to engage with experience based promotion by holding events at the sites of the investments and inviting local people to take part, thus drawing attention of media. Communication focused on particular contributions and individual experiences helped in de-linking the policy from the macroeconomic trends and structural reforms where, ironically, Cohesion policy was increasingly filling the gap left by the other policies and was consequently also taking the blame of the various policy failures.

While the Cohesion policy has an important stake in keeping the EU together, as the Slovenian case shows, it cannot and should not be seen as a mechanism for fixing all of the problems related with the asymmetrical crises. Rather than that, to avoid the expectations-capability gap, it should be based on reasonable expectations concerning specific contributions with a potential of spin offs and inspiring broader change

Marko Lovec COHESIFY Research Fellow at Central European University Center for Policy Studies