“There is no proportionality.” This is the chorus I have been hearing from policy stakeholders in Ireland as well as at the COHESIFY final conference held in April.

“Working in a million € programme is not the same as working in a billion € programme.”

True. The budgets of the programmes and the EU’s contribution are smaller. The investment priorities are more concentrated and the scale of the impact is different. Therefore, it is not surprising that national and regional authorities can be sceptical about the COHESIFY recommendations to raise the profile of communication activities in Cohesion Policy.

More developed regions raise three arguments about the communication of Cohesion Policy. First, in developed regions (“million € programme regions”), the impact of Cohesion Policy is small compared to cohesion countries or less developed regions (“billion € programme regions”) due to smaller budgets. Therefore, they claim that the expectations from programme communication need to be different, i.e. proportional to the scope and budgets of programmes.

Second, in more developed regions the EU funds up to 50 per cent of the value of programmes, while domestic funding sources cover the rest of the funding. In comparison, the EU can provide up to 85 per cent of the funds for programmes in the cohesion countries and less-developed regions of the EU. Why would anyone brand a project as European, when the EU provided half of the funding?

Third, small programmes tend to have fewer human resources available to work on communication or dedicated exclusively to communication tasks. In some of these programmes, communication officers work on a part-time basis or have additional programme administration responsibilities beyond communication.

These are fair points. Unfortunately, as one of the Irish policy stakeholders I interviewed put it: “We have been saying this message [missing proportionality] for years now, but it has fallen on deaf ears.” If a repeated message is not heard, then one might as well start to think differently about the issue.

Most of the communication about Cohesion Policy has been focused on its material benefits: number of jobs and supported businesses or kilometres of built roads. If you manage a million € programme, the number of businesses you can support with EU funds will be lower compared to a billion € programme. This is not only because the programme is that much smaller, but also because the nature of the projects supported changes. For example, if the programme concentrates mainly on SME development, the publicity billboards on projects will be less visible to people than a large billboard on a motorway connecting two major cities funded by an infrastructure-focused programme.

True. The budgets of the programmes and the EU’s contribution are smaller. The investment priorities are more concentrated and the scale of the impact is different. Therefore, it is not surprising that national and regional authorities can be sceptical about the COHESIFY recommendations to raise the profile of communication activities in Cohesion Policy.

More developed regions raise three arguments about the communication of Cohesion Policy. First, in developed regions (“million € programme regions”), the impact of Cohesion Policy is small compared to cohesion countries or less developed regions (“billion € programme regions”) due to smaller budgets. Therefore, they claim that the expectations from programme communication need to be different, i.e. proportional to the scope and budgets of programmes.

Second, in more developed regions the EU funds up to 50 per cent of the value of programmes, while domestic funding sources cover the rest of the funding. In comparison, the EU can provide up to 85 per cent of the funds for programmes in the cohesion countries and less-developed regions of the EU. Why would anyone brand a project as European, when the EU provided half of the funding?

Third, small programmes tend to have fewer human resources available to work on communication or dedicated exclusively to communication tasks. In some of these programmes, communication officers work on a part-time basis or have additional programme administration responsibilities beyond communication.

These are fair points. Unfortunately, as one of the Irish policy stakeholders I interviewed put it: “We have been saying this message [missing proportionality] for years now, but it has fallen on deaf ears.” If a repeated message is not heard, then one might as well start to think differently about the issue.

Most of the communication about Cohesion Policy has been focused on its material benefits: number of jobs and supported businesses or kilometres of built roads. If you manage a million € programme, the number of businesses you can support with EU funds will be lower compared to a billion € programme. This is not only because the programme is that much smaller, but also because the nature of the projects supported changes. For example, if the programme concentrates mainly on SME development, the publicity billboards on projects will be less visible to people than a large billboard on a motorway connecting two major cities funded by an infrastructure-focused programme.

While a large-scale programme or project might be easier to communicate, a small impact programme or project does not need to be a disadvantage. The communication could for instance be focused on European solidarity, rather than the bare material benefits. Moreover, many smaller programmes concentrate the EU funding on fewer projects which should make it easier to communicate about individual projects.

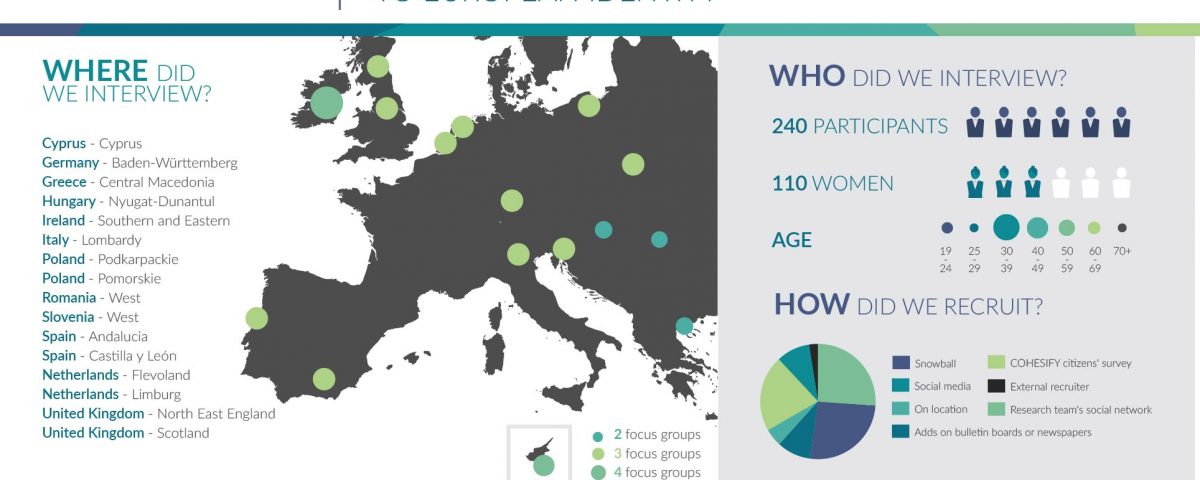

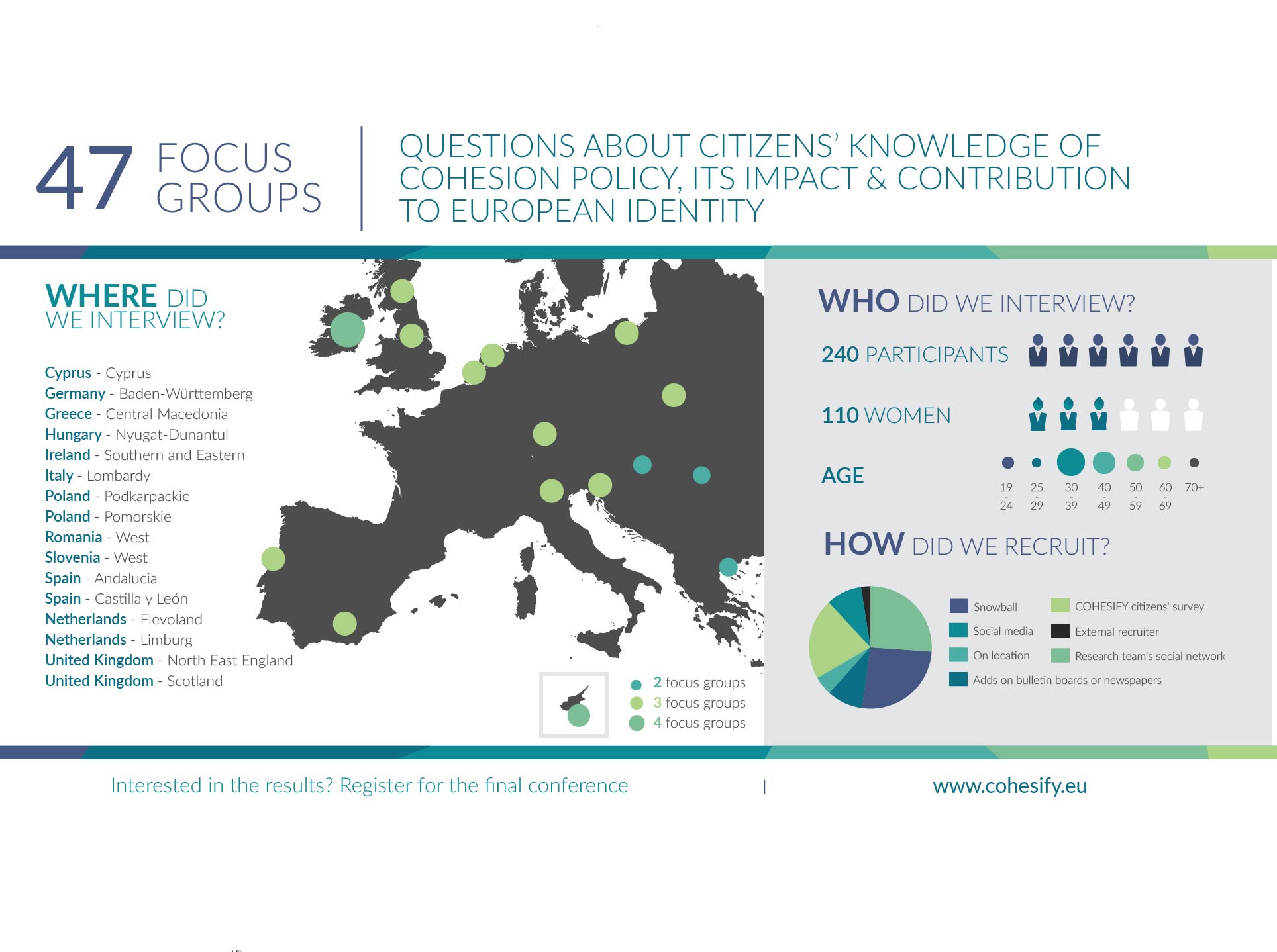

This is supported in the research we conducted in COHESIFY where we spoke to 240 EU citizens living in 16 EU regions across 12 EU countries. While it is true that most of the citizens we asked understood Cohesion Policy to be a development policy, many felt that they did not understand how the policy or the EU worked. Moreover, Cohesion Policy did not help them grasp better the functioning of the EU.

This is a missed opportunity, which shows that Cohesion Policy communication can be more than communicating its economic impact and material benefit. More than any other common policy of the EU, Cohesion Policy is catered to the citizen. It is based on principles of solidarity, cooperation and partnership. There is a need to discuss more the general principles of the EU not least because the clarity of a political system increases citizens’ participation.

For example, if citizens understood that that European, national and regional authorities work together in the EU and that Cohesion Policy is a partnership between them, then striking the branding balance between EU and national funders would not be so difficult. (Our research in fact shows that the partnership and solidarity principles are poorly understood). As it stands now, people bicker about the size and number of promotional logos. There is a belief among politicians that citizens can be fooled over who is to credit for the successes and who is to blame for the failures, while for a long time EU funds have been a matter of partnership and shared responsibilities.

Finally, if you are still not convinced that the Cohesion Policy communication can be about more than economic benefits, think about a post-Brexit Britain in the way one of our focus group participants did:

“I suppose if the economic aspect fails or if Britain leaves Europe and becomes wildly successful after… Then, I suppose you could have other Member States kind of looking at the economic benefit of actually being within Europe. So, thinking more broadly about the EU might be a long-term advantage as opposed to things at the moment.”

This is supported in the research we conducted in COHESIFY where we spoke to 240 EU citizens living in 16 EU regions across 12 EU countries. While it is true that most of the citizens we asked understood Cohesion Policy to be a development policy, many felt that they did not understand how the policy or the EU worked. Moreover, Cohesion Policy did not help them grasp better the functioning of the EU.

This is a missed opportunity, which shows that Cohesion Policy communication can be more than communicating its economic impact and material benefit. More than any other common policy of the EU, Cohesion Policy is catered to the citizen. It is based on principles of solidarity, cooperation and partnership. There is a need to discuss more the general principles of the EU not least because the clarity of a political system increases citizens’ participation.

For example, if citizens understood that that European, national and regional authorities work together in the EU and that Cohesion Policy is a partnership between them, then striking the branding balance between EU and national funders would not be so difficult. (Our research in fact shows that the partnership and solidarity principles are poorly understood). As it stands now, people bicker about the size and number of promotional logos. There is a belief among politicians that citizens can be fooled over who is to credit for the successes and who is to blame for the failures, while for a long time EU funds have been a matter of partnership and shared responsibilities.

Finally, if you are still not convinced that the Cohesion Policy communication can be about more than economic benefits, think about a post-Brexit Britain in the way one of our focus group participants did:

“I suppose if the economic aspect fails or if Britain leaves Europe and becomes wildly successful after… Then, I suppose you could have other Member States kind of looking at the economic benefit of actually being within Europe. So, thinking more broadly about the EU might be a long-term advantage as opposed to things at the moment.”

Andreja Pegan

Trinity College Dublin